If you look up at the sky at night, you will see a gorgeous nebula of luminescent stars. If you’re lucky enough, you could spot a planet. Recently, I was lucky enough to see Jupiter without using a telescope. Have you ever wondered how long it would take you to travel there? A trip by rocket to Jupiter would take around 600 days, which is about one and a half years. If you decide to travel to a star visible in the sky, it will take thousands upon thousands of years to travel there, even with the innovative technology and rockets that NASA and other space programs have been engineering. Are you stunned yet? How long would it take to travel to a black hole in the middle of another galaxy, specifically, the M87 black hole? If you’re traveling in the Voyager 1 spacecraft, it will take approximately 970 billion years to reach the M87 black hole. If you still aren’t shocked, I’m sure you will be after reading this; recently, a graduate student from MIT has discovered how to correctly generate an image of a black hole, the M87, even from its far distance.

How Do Scientists Spot a Black Hole?

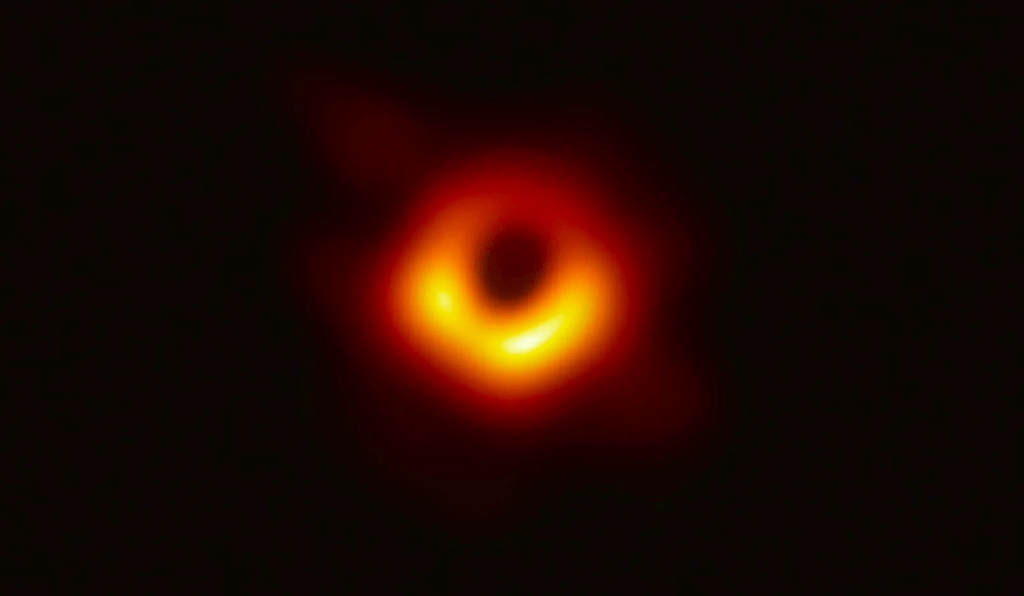

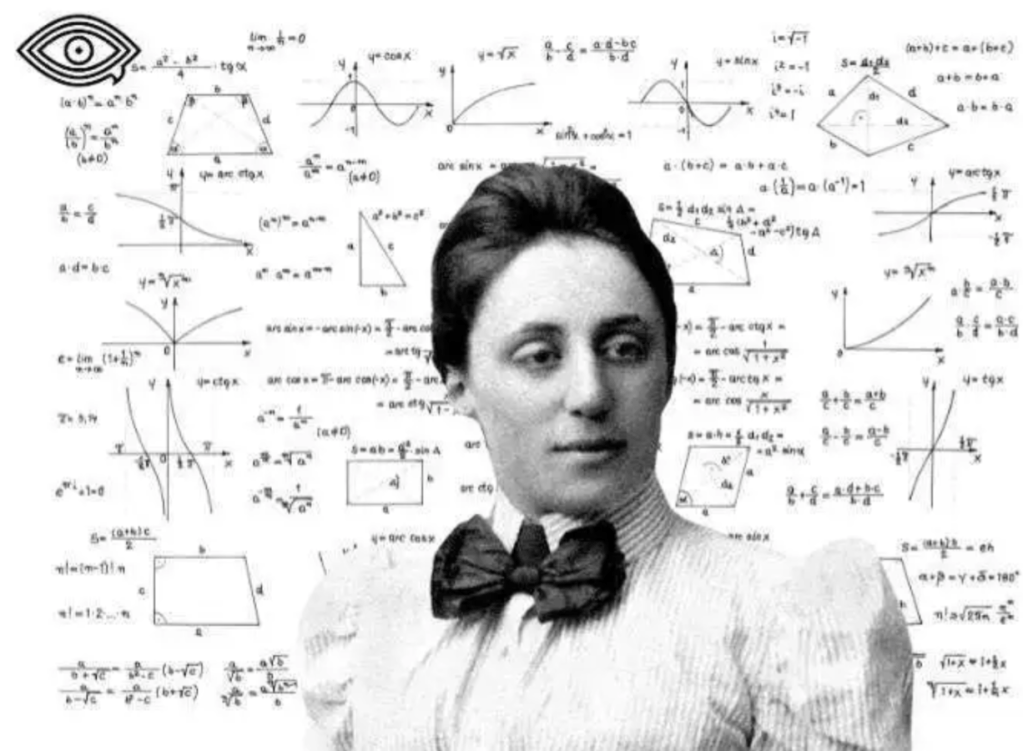

Chances are, you can picture what a black hole looks like in your mind. We have seen many of their images in articles, books, websites, etc. However, most of these images are biased to what we perceive these black holes to appear as. Luckily, thanks to Katie Bouman, a graduate student studying computer science at MIT, we are starting to understand how to correctly image a black hole using modern radio telescopes thanks to an algorithm called CHIRP (Continuous High-resolution Image Reconstruction using Patch priors). However, first, we must understand how we can even capture an image of a black hole since they are essentially invisible, as their gravitational pull is so intense that nothing, not even light, can escape. To be able to spot a black hole, scientists observe the effect that black holes have on objects that surround them. Scientists can predict these signs of a black hole due to Einstein’s theory of relativity, published in 1915. Einstein’s general theory of relativity predicted that massive objects, like black holes, warp the fabric of spacetime around them. The equations of general relativity that Einstein created allowed scientists to model the behavior of light and matter around these black holes, including how they would appear to us from Earth. One of the effects that scientists have found is that, usually, hot plasma (ionized gas) orbits around the black hole, making it appear as a dark sphere since the plasma emits light. This is called gravitational lensing, where objects behind the black hole are bent around it due to the black hole’s strong gravity, making a bright ring appear around it, casting a shadow of the black hole’s event horizon, the spot where nothing can escape from the black hole.

An Earth-Sized Telescope

So great, now we know that black holes can be spotted, due to the shadow of the event horizon. But how is the image captured? To capture the image of a black hole, scientists use radio waves instead of visible light. Radio waves can penetrate the dense gas and dust that surrounds black holes, which is something visible light cannot do. The Event Horizon Telescope (EHT), which is a network of radio telescopes distributed across the globe which observe black holes and other astronomical objects, captures these radio waves from various locations around the world, which are then combined to form a detailed image of the black hole. But as I’ve said before, the distance from Earth to the M87 black hole is extremely far. So far, that if every human being who has ever lived on Earth from the start of humanity to the present day could take a step toward the M87 black hole, the collective distance traveled would still be short by millions of years if we were trying to reach it. If a singular radio telescope were to capture an image of a black hole, it would have exceptionally low resolution and be useless to scientists. The resolution of the image a radio telescope can generate is fundamentally linked to its size and the wavelength of the radio waves it observes. Therefore, to accurately generate a high-resolution image of the M87 black hole, we would need a telescope the size of the Earth. Since that’s impossible, that’s where the importance of the EHT collaboration comes into play. Scientists have created the EHT to create an Earth-sized virtual telescope needed to capture the necessary resolution of the image. Combining data from these radio telescopes was essential because a single radio telescope, even one as large as the Arecibo Observatory before its collapse or the Green Bank Telescope, wouldn’t have the needed resolution on its own to capture such high-resolution images of such distant objects, like the M87 black hole.

The Algorithm

Although the EHT was necessary to get images of black holes, it is the CHIRP algorithm that essentially takes raw and noisy data and makes it into a clear picture. Even with all these telescopes working together, there are still missing gaps in the larger image that need to be filled in. To understand how this works, I’ll give you an example. Pretend you want to put together a massive mosaic artwork. However, upon opening the box and beginning to place the pieces on a large board, you realize that you have multiple missing pieces of the artwork. These missing pieces of the mosaic represent the incomplete data that the EHT network had to work with due to the limited number of telescopes. Regardless of the missing pieces of the mosaic, you can recognize familiar colors and patterns of the pieces due to your common knowledge and can predict where the pieces go. That is the technique that the CHIRP algorithm uses, called “patch priors”. In the algorithm, it is given various images. These include selfies, everyday items, astronomical objects, etc. This allows the algorithm to familiarize itself with visual features and patterns, giving it a sense of ‘common knowledge’ and enabling it to efficiently fill in the gaps of the image without being biased by our own perceptions of what a black hole should look like. It does this by using several smart algorithms to accurately fill in the incomplete data based on the information it already has and the images that it was given. In simple terms, the CHIRP algorithm completes missing data, and as a result, generates a clear and high-resolution image. However, to make sure this image is accurate, there are also several regularization techniques in the algorithm to make sure it doesn’t focus on too many unrealistic details, so the image comes out looking concise and realistic. After the algorithm was refined over several years, the EHT collaboration revealed the first image of the M87 black hole in April 2019. This announcement was a huge accomplishment and stunned people around the world.

Overall, even with her limited knowledge in the field, Katie shocked the entire world in 2019 with her algorithm and the countless contributions she made to science. One example of this, she introduced new methods that astronomers can use to fill in incomplete data and showed how important it is to mix different expertise areas. Even though she was new to astrophysics, the new and fresh ideas that she brought to the table proved that the right amount of hard work could change science entirely, and showed the importance and benefit that different views can have on solving complex problems.

Works Cited

Brewis, Harriet. “Grad student Katie Bouman created the algorithm that led to the first-ever black hole photo.” The Standard, 12 Apr. 2019, http://www.standard.co.uk/news/world/mit-grad-student-katie-bouman-algorithm-black-hole-photo-a4114946.html. Accessed 14 Aug. 2024.

Hardesty, Larry. “A method to image black holes.” MIT News, 6 June 2016, news.mit.edu/2016/method-image-black-holes-0606. Accessed 14 Aug. 2024.

Overbye, Dennis. “Darkness Visible, Finally: Astronomers Capture First Ever Image of a Black Hole.” The New York Times, © 2024 The New York Times Company, 10 Apr. 2019, http://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/10/science/black-hole-picture.html. Accessed 13 Aug. 2024.

“Scientist superstar Katie Bouman designed algorithm for black hole image.” Phys Org, © 2019 AFP, 11 Apr. 2019, phys.org/news/2019-04-scientist-superstar-katie-bouman-algorithm.html. Accessed 14 Aug. 2024.

Shu, Catherine. “The creation of the algorithm that made the first black hole image possible was led by MIT grad student Katie Bouman.” TechCrunch, 10 Apr. 2019, techcrunch.com/2019/04/10/the-creation-of-the-algorithm-that-made-the-first-black-hole-image-possible-was-led-by-mit-grad-student-katie-bouman/. Accessed 14 Aug. 2024.

About the Author

Hello! My name is Ariana, and I am an incoming freshman at East High School. I’m passionate about STEM and love learning how things work, especially in psychology and biology.

Leave a comment