As of July 1943, World War II is in full swing–and the city of Kursk, Russia, is in chaos. A massive confrontation between Germans and Soviets is underway, including over 2.6 million troops, nearly 5,300 aircraft, and over 7,000 tanks–in fact, this is considered the largest tank battle in history.

Germany is in dire need of a win after their devastating loss in the Battle of Stalingrad six months earlier. The grueling Russian winter, lack of resources, and Adolf Hitler’s stubborn refusal to retreat resulted in 2 million deaths for both Soviets and Germans, civilians and soldiers alike. Still, it was a point in favor of the Allies and a huge blow to Germany’s persistent expansion–and Soviets are determined to continue the momentum.

But the Germans take a page out of their adversary’s playbook. The fight in Kursk is concentrated around the Kursk salient–a bulge in Russian forces. They aim to eliminate this obstacle by conducting a pincer attack, where they’ll flank it by the north and south and crush it into submission–exactly what was done to them before.

Titled “Operation Citadel,” the mission leads Germany to amass the aforementioned forces, with a special focus on new Panther and Tiger tanks–equipped with superior firepower, protection, and mobility compared to Russia’s mass-produced T-34.

Finally, after months of planning and delay, Germany readies itself for the kill. And on July 5, it strikes, intent on decimating Soviet forces and reassuming dominance in the war.

However, when Germans advance upon the salient, they’re met with one shock after another, including extensive anti-tank ditches and minefields, withdrawn enemy forces, and a preemptive artillery barrage. Their numbers, expected to overwhelm, are soon crushed by a staggering Soviet force.

The element of surprise, perhaps the most crucial aspect of wartime strategy, slips through Germany’s fingers. Even more surprising? Thanks to Bletchley Park and its courageous codebreakers, they never had a hold on it in the first place.

Years before, on November 1, 1919, the Government Code and Cipher School was officially founded. It merged the Admiralty’s Room 40 and MI1(b), both of which were UK military intelligence groups founded in the beginning of WWI. Information gleaned from both efforts helped to combat German air raids, intercept the famous Zimmerman telegram that drew the US into the war, and offered insight regarding Germany’s naval movements ahead of the Battle of Jutland.

GC&CS’s goal was to protect British government communications and decrypt those sent by other countries. In preparation for WWII, personnel began relocating from London to Bletchley Park in 1939. Tucked away in rural Milton Keynes, England, the idea was to find a discreet place to work, away from the danger of war.

Headquarters were secured, but choosing people to staff it would be more arduous. Guidelines for recruitment included “men of the professor type,” primarily from the prestigious Oxford and Cambridge universities. Notable men like Alan Turing and Gordon Welchman were enlisted early on, as well as codebreaking veterans who served in WWI such as Dilly Knox and Nigel de Grey. Mathematicians, crossword fanatics, and linguists were especially sought out, as their talents would come in handy for unscrambling code.

For example, The Daily Telegraph was a newspaper that, after facing allegations of easy crosswords, hosted a competition to see who could solve a much harder one in twelve minutes. Five people managed it–and some were then contacted by the British government about a “matter of national importance”–essentially, Bletchley. Even so, as the war began and volume of intercepts grew exponentially, Bletchley Park needed a new source of workers. And with most men joining the military to fight, they turned to the only people left: women.

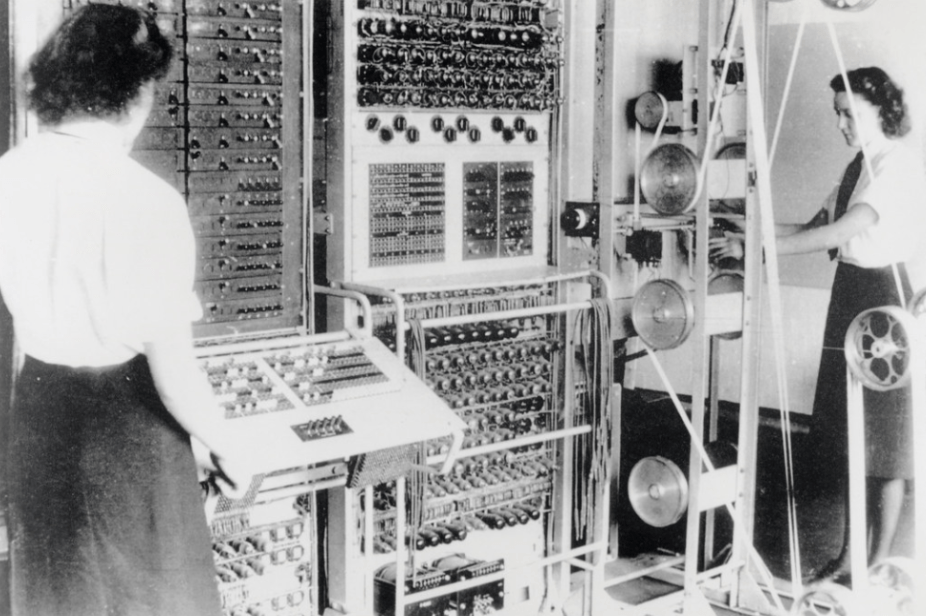

They were initially recruited from the aforementioned universities, then from organizations like the Women’s Royal Naval Service, the Auxiliary Territorial Service, and the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force as demand grew. By the end of the war, women comprised over 75% of Bletchley’s total forces.

Several codes were tackled in Bletchley Park’s hastily built huts, including the Lorenz cipher (nicknamed “Tunny”), as well as those created by the German Siemens and Halske T52 machines (“Fish” and “Sturgeon,” respectively). However, none are more famous–or infamous–than the daunting Enigma.

Enigma was generated by a typewriter-esque machine, which scrambled letters through a series of rotors and a plugboard. This turned crucial information into gibberish that could only be decoded if one knew the setting–which was changed daily, at midnight.

But what differentiated it from other ciphers? One answer is the dizzying amount of combinations allowed. Enigma implemented polyalphabetic substitution, which meant the same letter could be encoded differently in one message depending on the specific rotor positions during each keystroke. Pairs of the letter and its jumbled counterpart were also swapped by the plugboard before and after encryption. The overall combination of rotor choices, orders, and positions, as well as ring settings and plugboard connections resulted in nearly 159 quintillion setting possibilities (159,000,000,000,000,000,000)!

Brute-forcing this many options was downright impossible considering limited resources and time. So, how did the Allies crack it?

The work began with Poland in the years before WWII. Mathematician Marian Rejewski accurately deduced the inner workings of Enigma entirely from his calculations. Fellow math expert Henryk Zygalski invented perforated paper sheets that helped determine rotor settings. However, after Germany’s invasion, the torch was passed to Britain, and to some extent, the United States. By this point, Enigma was much stronger–but the amount of information to analyze was much larger, making it easier to spot patterns and repetitions.

There were multiple ways to confront the code. One was to hunt for clues by looting enemy command posts and wrecked ships, and conducting intelligence operations (think spycraft). This amalgamation of sources revealed details of the Enigma’s mechanisms and execution. Another method used was cryptanalysis, in which dozens and dozens of messages were examined for cribs. Cribs were plaintext words hypothesized to exist in any message. These were incredibly useful for ruling out Enigma settings, all due to a fatal flaw in the machine.

Due to a reflector component, no letter could ever be encoded as itself. For example, if one were to scramble the words “HER STEM SPACE” with Enigma, there would never be an “H” in the first blank, an “E” in the second, and so on. This seemingly inconsequential defect proved crucial for the Allies and critical for Germany, because they could align common phrases such as “Heil Hitler” and “weather report” with similarly sized chunks of code. If any letter matched up, they could rule out that setting for Enigma for the day, which helped reduce potential possibilities.

The prospect of repeating this hundreds, if not thousands of times a day was incredibly daunting and surely fruitless. Luckily, Turing and Welchman created the bombe machine that systematically tested possible Enigma settings. It compared the many possibilities against suspected cribs and significantly accelerated the decryption process.

From recruitment to crib identification to the thousands of hours invested in its operations, Bletchley Park was ambitious, notoriously secretive, and incredibly successful. Many developments, whether directly or indirectly, sprang from it–such as the recognition of women’s abilities, advancement of codebreaking, and the preservation of the free world. Many important battles, like the previously mentioned Battle of Kursk, the Battle of the Atlantic, and the battle of Cape Matapan were all Allied victories thanks to BP intelligence. In fact, it’s estimated that BP shortened the war by nearly two years–and with it, unnecessary casualties, money, and time.

Bletchley Park did more than crack code–it saved lives. And while most of the workers’ identities remain a secret, every single one of them is a hero–without which victory may have been impossible, and with it, the world we know today.

Works Cited

“Alan Turing and the Hidden Heroes of Bletchley Park.” The National WWII Museum, 24 June 2020, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/alan-turing-betchley-park. Accessed 18 July 2025.

“As a Location | Bletchley Park.” Bletchley Park, http://www.bletchleypark.org.uk/news-and-media/as-a-location/#:~:text=For%20Film%20Crews,Getting%20here.

“Battle of Kursk.” History.com, 29 October 2009, https://www.history.com/articles/battle-of-kursk. Accessed 2 July 2025.

“Battle of Kursk – Seventeen Moments in Soviet History.” Seventeen Moments in Soviet History, https://soviethistory.msu.edu/1943-2/battle-of-kursk/. Accessed 2 July 2025.

Beyer, Greg. “Battle of Kursk: The Largest Tank Battle in History.” TheCollector, 31 Jan. 2024, http://www.thecollector.com/battle-of-kursk/#:~:text=The%20Germans%20wanted%20to%20launch,were%20supported%20by%201%2C800%20aircraft.&text=The%20months%20of%20German%20buildup,the%20strength%20of%20both%20armies. Accessed 18 July 2025.

Cartwright, Mark. “Battle of Kursk: Largest Tank Battle in History.” World History Encyclopedia, 28 April 2025, https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2704/battle-of-kursk/. Accessed 2 July 2025.

Coultas, Charles. “Tunny and Heath Robinson — The National Museum of Computing.” The National Museum of Computing, https://www.tnmoc.org/tunny-heath-robinson. Accessed 18 July 2025.

“Enigma Machine.” CIA, https://www.cia.gov/legacy/museum/artifact/enigma-machine/. Accessed 18 July 2025.

“Enigma Machine.” Brilliant, https://brilliant.org/wiki/enigma-machine/. Accessed 18 July 2025.

“E163 – the Women of Newnham College | Bletchley Park.” Bletchley Park, 27 Feb. 2025, http://www.bletchleypark.org.uk/our-story/e163-the-women-of-newnham-college/#:~:text=Women%20were%20the%20backbone%20of,and%20in%20other%20wartime%20roles.

Halfond, Irwin. “Tank Battle at Kursk Devastates German Forces.” EBSCO, https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/military-history-and-science/tank-battle-kursk-devastates-german-forces. Accessed 2 July 2025.

Hart, Basil Liddell. “Battle of Kursk | Eastern Front, German Offensive, Soviet Counterattack.” Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/event/Battle-of-Kursk. Accessed 2 July 2025.

Hollingum, Ben. “Tank Clash – The German Panther vs. the Soviet T-34-85 – MilitaryHistoryNow.com.” Military History Now, 20 March 2015, https://militaryhistorynow.com/2015/03/20/tank-clash-the-german-panther-vs-the-soviet-t-34-85/. Accessed 2 July 2025.

“How the Allies cracked the Enigma machine.” NordVPN, https://nordvpn.com/blog/cracking-the-enigma/. Accessed 18 July 2025

Kaushanov, Ria Novosti Archive Image #1274 /. V., and Ria Novosti Archive Image #1274 /. V. Kaushanov. “Red Army T34 Tanks.” World History Encyclopedia, 3 Apr. 2025, http://www.worldhistory.org/image/20310/red-army-t34-tanks.

Monk, Chris. “Wrens Operating the ‘Colossus’ Computer, 1943.” Flickr, http://www.flickr.com/photos/101251639@N02/9669449367.

Newstalk. “How Crossword Puzzles Won the Second World War.” Newstalk, 23 Oct. 2014, http://www.newstalk.com/news/how-crossword-puzzles-won-the-second-world-war-685215#:~:text=second%20World%20War-,Newstalk,to%20break%20German%20military%20code..

“Our origins & WWI.” GCHQ, https://www.gchq.gov.uk/section/history/our-origins-and-wwi. Accessed 18 July 2025.

“Our origins & WWI.” GCHQ, https://www.gchq.gov.uk/section/history/our-origins-and-wwi. Accessed 18 July 2025.

“Who Were the Codebreakers? | Bletchley Park.” Bletchley Park, 23 Feb. 2022, http://www.bletchleypark.org.uk/our-story/who-were-the-codebreakers/#:~:text=By%201945%2C%2075%25%20of%20the%20staff%20of,worked%20alongside%20each%20other%20in%20most%20sections.

About the Author

Anjana is interested in medicine and developing fields within it, especially antimicrobial resistance. She is passionate about reading and writing, and merging words and healthcare in an empowering way is her life’s goal.

Leave a comment