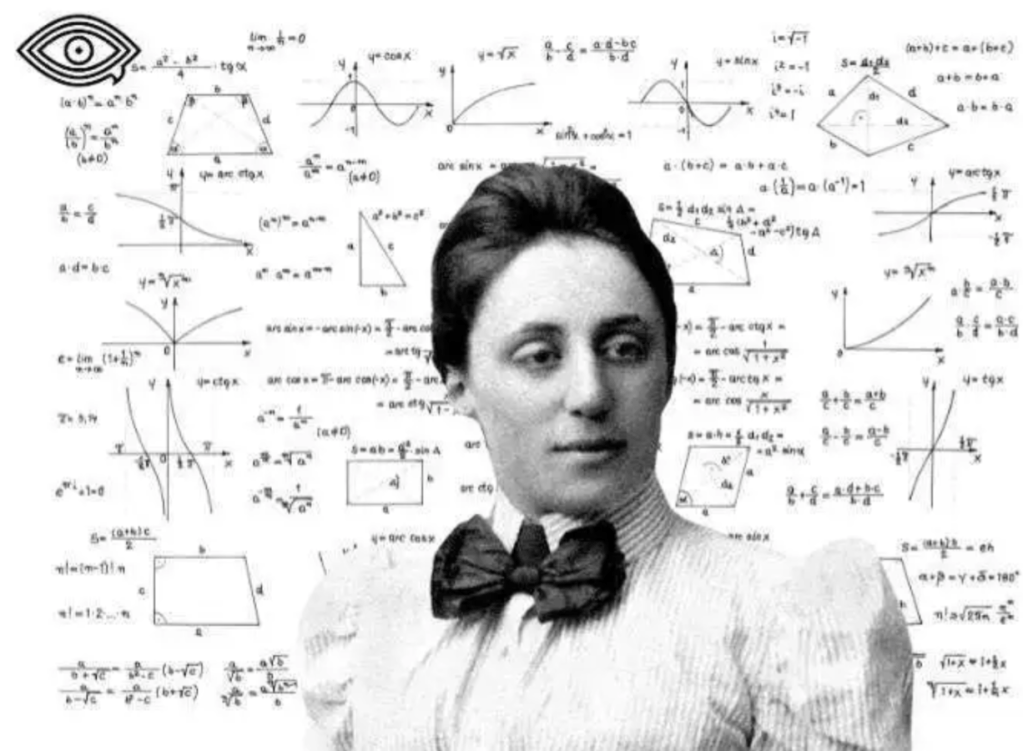

In the early twentieth century, when women were systematically excluded from academia, one mathematician defied every barrier placed before her to revolutionize the field of mathematics forever. Amalie Emmy Noether, born on March 23, 1882, in Erlangen, Germany, would become what Albert Einstein called the “most significant creative mathematical genius thus far produced since the higher education of women began” (Emmy Noether). Despite facing relentless gender discrimination and later persecution under Nazi rule, Noether transformed abstract algebra and made fundamental contributions to theoretical physics that continue to shape modern science.

Noether’s journey to mathematical greatness was fraught with obstacles from the beginning. When she first sought to study mathematics at the University of Erlangen in 1900, women were not permitted to formally enroll, forcing her to audit classes unofficially with individual professors’ permission (Emmy Noether). She spent a semester at the University of Göttingen studying under renowned mathematicians David Hilbert, Felix Klein, and Hermann Minkowski before returning to Erlangen when the rules finally changed in 1904 to allow women as full students (Emmy Noether). In 1907, she earned her doctorate summa cum laude, becoming only the second woman to receive a Ph.D. in mathematics from a German university (Combe).

For the next seven years, Noether worked at the University of Erlangen without pay or official title, assisting her father, mathematician Max Noether, and conducting her own research. Her unpaid labor exemplified the systemic barriers women faced in academia—despite possessing exceptional talent and credentials, she was denied the basic recognition and compensation afforded to her male counterparts. In 1915, David Hilbert and Felix Klein invited her to join the prestigious University of Göttingen to work on problems related to Einstein’s theory of general relativity. However, university faculty members vehemently opposed hiring a woman. Hilbert famously retorted, “I do not see that the sex of the candidate is an argument against her admission as Privatdozent. After all, we are a university, not a bathhouse” (O’Connor and Robertson).

Despite the resistance, Noether remained at Göttingen, initially teaching courses listed under Hilbert’s name. During this period, she developed what became known as Noether’s theorem—a fundamental result that reveals the deep connection between symmetry and conservation laws in physics. Published in 1918, this theorem demonstrated that every differentiable symmetry of a physical system corresponds to a conservation law. For instance, the symmetry of physical laws over time leads to the conservation of energy, while symmetry in space corresponds to the conservation of momentum. This insight has been described as “one of the most important mathematical theorems ever proved in guiding the development of modern physics” (Emmy Noether). The theorem became essential to quantum mechanics, particle physics, and string theory.

In 1919, Noether finally received permission to lecture under her own name, though she remained unpaid for another three years. It was during this period that she began her most revolutionary work in abstract algebra. Her 1921 paper Idealtheorie in Ringbereichen (Theory of Ideals in Ring Domains) fundamentally changed how mathematicians approached algebra. Rather than working with specific numbers or equations, Noether pioneered an abstract, conceptual approach that revealed underlying structures and relationships. She developed the theory of rings, fields, and modules, introducing what are now called Noetherian rings—mathematical structures that satisfy the ascending chain condition, a property she elegantly employed to prove powerful theorems (Emmy Noether).

Noether’s abstract approach represented a paradigm shift in mathematics. As colleague B.L. van der Waerden explained, she believed that “any relationships between numbers, functions, and operations become transparent, generally applicable, and fully productive only after they have been isolated from their particular objects and been formulated as universally valid concepts” (O’Connor and Robertson). This philosophy, sometimes called begriffliche Mathematik (purely conceptual mathematics), became the foundation of modern algebra. Mathematician Nathan Jacobson noted that her methods became so standard that “any textbook on abstract algebra bears the evidence of Noether’s contributions” (Emmy Noether).). Her influence extended far beyond her own publications—she was extraordinarily generous with her ideas, freely sharing insights that appeared in the work of other mathematicians, even in fields distant from her specialty.

Throughout the 1920s, Noether continued to publish groundbreaking work while mentoring a generation of mathematicians who became known as the “Noether school.” She also made significant contributions to algebraic topology, suggesting that topological properties be studied through algebraic structures—an approach that Heinz Hopf and Paul Alexandrov immediately adopted and which transformed the field. In 1932, she became the first woman invited to address the International Congress of Mathematicians in Zürich, and that same year received the Ackermann-Teubner Memorial Award alongside Emil Artin. Yet even at the height of her recognition, she was never promoted to full professor at Göttingen, a civil service position that would have provided proper compensation and security (Emmy Noether).

In 1933, when Adolf Hitler rose to power, the Nazi regime dismissed Jewish professors from German universities. Noether was among six faculty members at Göttingen who received telegrams ordering them to stop teaching immediately. Her response demonstrated characteristic resilience: “This thing is much less terrible for me than it is for many others,” she wrote to a colleague (Blanks). With assistance from the Rockefeller Foundation, Noether secured a position at Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania, where she finally worked at an institution that valued her as an equal. At Bryn Mawr, she collaborated with women mathematicians including department head Anna Pell Wheeler, who understood firsthand the struggles Noether had endured.

Tragically, Noether’s American career was cut short. In 1935, she underwent surgery to remove an ovarian cyst. Despite initial signs of recovery, she died on April 14, 1935, four days after the operation, at the age of 53. The cause was likely a viral infection. Her ashes were buried beneath the cloisters of Bryn Mawr’s M. Carey Thomas Library, a fitting resting place for a mathematician who spent her life fighting for women’s place in academia.

Emmy Noether’s legacy extends far beyond her lifetime. Her work laid the foundation for much of twentieth-century mathematics and physics. Terms like “Noetherian rings,” “Noetherian modules,” and “Noether normalization” appear throughout modern mathematics. An asteroid, 7001 Noether, bears her name. In 2019, Time magazine named her the “Woman of the Year” for 1921 in their series celebrating overlooked women throughout history. Hermann Weyl, one of the twentieth century’s leading mathematicians, wrote that Noether “changed the face of algebra by her work” (Emmy Noether). Yet perhaps her greatest legacy lies in the path she forged for women in mathematics and science- a path carved through systematic discrimination and persecution, paved with brilliant insights and unwavering dedication to knowledge.

Works Cited

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. “Emmy Noether | German Mathematician.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 19 Mar. 2019, http://www.britannica.com/biography/Emmy-Noether.

“Emmy Noether – Biography.” Maths History, 2024, mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Noether_Emmy/.

Wikipedia Contributors. “Emmy Noether.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 12 Jan. 2026.

“Emmy Noether.” Agnesscott.org, 2019, mathwomen.agnesscott.org/women/noether.htm.

Blanks, Tamar Lichter. “Math Genius Emmy Noether Endured Sexism and Nazism. 100 Years Later, Her Ideas Still Ring True.” Live Science, 17 July 2021, http://www.livescience.com/emmy-noether-unrecognized-contributions-modern-math.html.

““Without Emmy Noether, There Would Be a Huge Gap in Mathematics and Its Understanding.”” http://Www.mpg.de, 2018, http://www.mpg.de/16548098/emmy-noether.

About the Author

Hi! My name is Fatima Boganee and I’m 17 years old. I live in Mauritius and plan to work in biology when I’m older!

Leave a comment